• Winery

Vitello tonnato and the mayonnaise conundrum

Reading time in

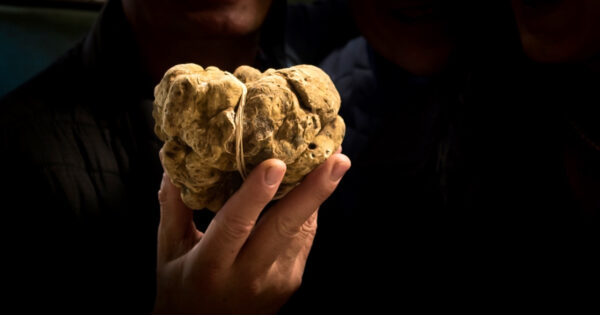

Above: A vitello tonnato sandwich, served to me some years ago in Barolo village.

Today’s post is the second in a series that I’m devoting to one of my favorite dishes from Piedmont and one of the region’s most beloved, vitello tonnato (veal with tuna sauce).

Click here for the first post in the series, wherein I have translated Pellegrino Artusi’s landmark recipe for the dish (La scienza in cucina e l’arte di mangiare bene [The Science of Cooking and the Art of Eating Well], 1891), which does not include mayonnaise.

Although the dish is commonly made with mayonnaise today, most Italian gastronomic pundits maintain that true vitello tonnato should be mayonnaise-free. And they often point to Artusi’s mayonnaiseless recipe, first published toward the end of the nineteenth century, as the original recipe. This attribution is owed in no small part to the fact that Artusi’s cookery book became wildly popular toward by the end of his lifetime. And today, it’s rare not to find a dog-eared copy on the shelves in the homes of the typical Italian family who often uses it for everyday and festive cooking (I can attest to this from my own experience in Italian homes).

It’s important to note that Artusi also included a recipe for mayonnaise in his game-changing tome.

His recipe number “126” is for “salsa maionese” (“mayonnaise sauce”), which he recommends to accompany poached fish. (You can read an English-language translation here.)

So it’s clear that he was aware of the mayonnaise but did not include it in his recipe for vitello tonnato. This fact would seem to indicate, definitively, that the use of mayonnaise was introduced much later.

Not much is known about the true origin of mayonnaise. The Wiki entry for mayonnaise is a useful aggregation of the competing theories and their sources. But the bottomline is that we really don’t know where it came from or why. Nor do we know with any real certainty the origin of its name.

What we do know is that the earliest recipes for mayonnaise begin to appear in France in the early 1800s (nearly 100 years before Artusi’s book).

And the fact that Artusi included it in his Scienza reflects its place in the European culinary canon at the time.

But, again, he recommends it for poached fish and not for meat and not for cured fish (like tuna).

The widespread (excuse the pun!) use of Pasteurized mayonnaise in the twentieth-century can probably be attributed to Richard Hellmann who popularized its application in the kitchen at his delicatessen on Columbus Ave. in Manhattan during the early 1900s. He ultimately abandoned his food shop by the end of the 1910s to devote himself exclusively to the production of mayonnaise.

I don’t have any proof of this but I speculate — all things considered — that it was during this era that people began to fold mayonnaise into cured tuna to make salads. It’s still popular today to add hard-boiled eggs to tuna salad and tuna salad and egg salad — both mayonnaise-based — are generally sold side-by-side today (as is potato salad, for that matter).

Anecdotally, I know that Pasteurized, jarred mayonnaise didn’t become popular in Italy until the era of economic renewal after the Second World War.

My dissertation advisor, Luigi Ballerini, who was born in Milan in 1940, once told me that when he first took his American fiancée home to meet his mother in the early 1970s, she requested mayonnaise with her meal (she was from New York).

His mother swiftly made mayonnaise from scratch just for her (probably using Artusi’s recipe!). I believe that this is an indication, supported by other anecdotal attestations, that mayonnaise wasn’t a “household” food product at the time.

The presence of American military and the growing sway of American cultural hegemony during the 60s and 70s in Italy also probably contributed to the rise in popularity of commercial mayonnaise.

And I believe that this was when the creamy stuff found its way into vitello tonnato.

This is not the last post in the series: Next I’ll look closely at the use of cured tuna and anchovies in Piedmont. And it’s possible that my research will reveal more insight into the mayonnaise conundrum.

To be continued…